The Cloward–Piven strategy could easily be called “socialism,” matter of fact, we wrote about it in the post Socialism History And The Flaws Of It, but there is one distinct difference. One is outright visible and the other is not so visible.

One would easily find that politicians would use the one that was not so visible as to not draw attention to themselves and the underlying objective that they would have in mind, which in 90% of the cases is money and power.

One such strategy is called the “The Cloward–Piven Strategy,” where a politician or group of politicians conspire to overload the system of government that they are supposed to represent.

In the US, there are a lot of politicians that have pushed for socialism; we’re sure to drain a lot of money out of the central banking system.

One does not have to look very far to see that a list of current politicians: Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Bernie Sanders, Chuck Schumer, Barack Obama and Joe Biden. To add further insult to injury, you can add any and all sanctuary cities to the list.

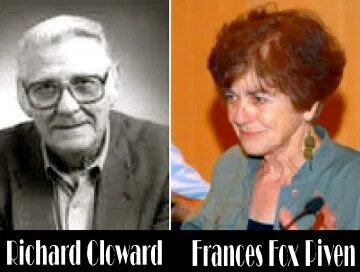

The Cloward–Piven strategy is a political strategy outlined in 1966 by American sociologists and political activists Richard Cloward and Frances Fox Piven. It is the strategy of forcing political change to societal collapse through orchestrated crises. The Cloward-Piven Strategy seeks to hasten the fall of capitalism by overloading the government bureaucracy with a flood of impossible demands, amassing massive unpayable national debt, and other methods such as unfettered immigration, thus pushing society into crisis and economic collapse.

Cloward and Piven were both professors at the Columbia University School of Social Work. The strategy was outlined in a May of 1966 an article in the liberal magazine The Nation titled “The Weight of the Poor: A Strategy to End Poverty.”

Cloward and Piven’s article is focused on forcing the Democratic Party, which in 1966 controlled the presidency and both houses of the United States Congress, to take federal action to help the poor. They stated that full enrollment of those eligible for welfare would produce bureaucratic disruption in welfare agencies and fiscal disruption in local and state governments that would deepen the existing divisions among elements in the big-city Democratic coalition – The remaining white middle class, the working-class ethnic groups and the growing minority poor. To avoid a further weakening of that historic coalition, a national Democratic administration would be constrained to advance a federal solution to poverty that would override local welfare failures, local class and racial conflicts and local revenue dilemmas.”

They further wrote “The ultimate objective of this strategy – to wipe out poverty by establishing a guaranteed annual income – will be questioned by some. Because the ideal of individual social and economic mobility has deep roots, even activists seem reluctant to call for national programs to eliminate poverty by the outright redistribution of income.

Michael Reisch and Janice Andrews wrote that Cloward and Piven “proposed to create a crisis in the current welfare system by exploiting the gap between welfare law and practice that would ultimately bring about its collapse and replace it with a system of guaranteed annual income. They hoped to accomplish this end by informing the poor of their rights to welfare assistance, encouraging them to apply for benefits and, in effect, overloading an already overburdened bureaucracy.”

The authors pinned their hopes on creating disruption within the Democratic Party by stating “Conservative Republicans are always ready to declaim the evils of public welfare, and they would probably be the first to raise a hue and cry. But deeper and politically more telling conflicts would take place within the Democratic coalition. Whites, both working class ethnic groups and many in the middle class would be aroused against the ghetto poor, while liberal groups, which until recently have been comforted by the notion that the poor are few would probably support the movement. Group conflict, spelling political crisis for the local party apparatus, would thus become acute as welfare rolls mounted and the strains on local budgets became more severe.”

Michael Tomasky, writing about the strategy in the 1990’s and again in 2011, called it “wrongheaded and self-defeating,” writing “It apparently didn’t occur to Cloward and Piven that the system would just regard rabble-rousing black people as a phenomenon to be ignored or quashed.”

In papers published in 1971 and 1977, Cloward and Piven argued that mass unrest in the US, especially between 1964 and 1969, did lead to a massive expansion of welfare rolls, though not to the guaranteed-income program that they had hoped for. Political scientist Robert Albritton disagreed, writing in 1979 that the data did not support this thesis. He offered an alternative explanation for the rise in welfare caseloads.

In his 2006 book “Winning the Race,” political commentator John McWhorter attributed the rise in the welfare state after the 1960’s to the Cloward–Piven strategy, but wrote about it negatively, stating that the strategy “created generations of black people for whom working for a living is an abstraction.”

According to historian Robert E. Weir in 2007 “Although the strategy helped to boost recipient numbers between 1966 and 1975, the revolution its proponents envisioned never transpired.”