Towards the end of the Vietnam war, the term “children of the dust” represented the children that were conceived by the foreign military men that fought in that war.

The striking resemblance of the song “Dust in the wind,” by the band Kansas, is a stark reminder of the dark time left in the minds of the mothers and children that were left behind. To the mothers and children, the feeling of life being meaningless; dreams and passions really mean nothing and that our aspirations and actions are insignificant.

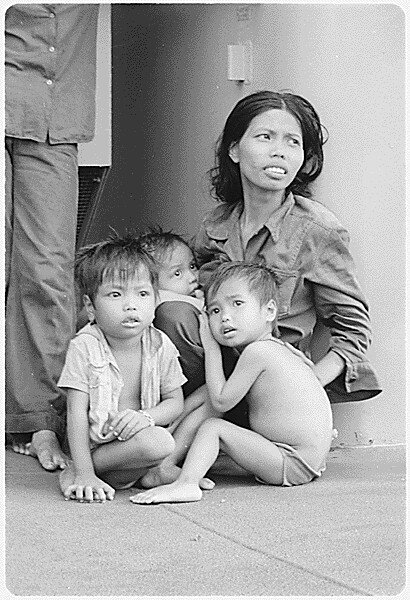

The children grew up as the leftovers of an unpopular war, straddling two worlds but belonging to neither. Most never knew their fathers. Many were abandoned by their mothers at the gates of orphanages. Some were discarded in garbage cans. Schoolmates taunted and pummeled them and mocked the features that gave them the face of the enemy, round blue eyes and light skin, or dark skin and tight curly hair if their fathers were African-Americans. Their destiny was to become waifs and beggars, living in the streets and parks of South Vietnam’s cities, sustained by a single dream: to get to America and find their fathers.

But neither America nor Vietnam wanted the kids known as Amerasians and commonly dismissed by the Vietnamese as “children of the dust” as insignificant as a speck to be brushed aside. The care and welfare of these unfortunate children has never been and is not now considered an area of government responsibility,” the US Defense Department said in a 1970 statement. “Our society does not need these bad elements,” the Vietnamese director of social welfare in Ho Chi Minh City (Saigon) said a decade later. As adults, some Amerasians would say that they felt cursed from the start.

In early April of 1975, Saigon was falling to Communist troops from the north and rumors spread that southerners associated with the US might be massacred, President Gerald Ford announced plans to evacuate 2,000 orphans, many of them Amerasians. Operation Babylift’s first official flight crashed in the rice paddies outside Saigon, killing 144 people, most of them children. South Vietnamese soldiers and civilians gathered at the site, some to help, others to loot the dead. Despite the crash, the evacuation program continued another three weeks.

No one knows how many Amerasians were born, and ultimately left behind in Vietnam during the decade-long war that ended in 1975. In Vietnam’s conservative society, where premarital chastity is traditionally observed and ethnic homogeneity embraced, many births of children resulting from liaisons with foreigners went unregistered. According to the Amerasian Independent Voice of America and the Amerasian Fellowship Association.

Advocacy groups recently formed in the US, contemplated that no more than a few hundred Amerasians remain in Vietnam; the groups would like to bring all of them to the US. The others, some 26,000 men and women now in their 30s and 40s, together with 75,000 Vietnamese they claimed as relatives began to be resettled in the US after Representative Stewart McKinney of Connecticut called their abandonment a “national embarrassment” in 1980 and urged fellow Americans to take responsibility for them.

Unfortunately, no more than three percent found their fathers in their adoptive homeland. Good jobs were scarce. Some Amerasians were vulnerable to drugs, became gang members and ended up in jail. As many as half remained illiterate or semi-illiterate in both Vietnamese and English and never became US citizens. The mainstream Vietnamese-American population looked down on them, assuming that their mothers were prostitutes, which was sometimes the case, though many of the children were products of longer-term, loving relationships, including marriages.

Mention Amerasians and people would roll their eyes and recite an old saying in Vietnam “Children without a father are like a home without a roof.”

The massacres that President Ford had feared never took place, but the Communists who came south after 1975 to govern a reunited Vietnam were hardly benevolent rulers. Many orphanages were closed, and Amerasians and other youngsters were sent off to rural work farms and reeducation camps. The Communists confiscated wealth and property and razed many of the homes of those who had supported the American-backed government of South Vietnam. Mothers of Amerasian children destroyed or hid photographs, letters and official papers that offered evidence of their American connections.

Family members scattered throughout the Philippines, negotiating their futures with the US Embassy in Manila. For a decade, the Philippines had been a sort of halfway house where Amerasians could spend six months, learning English and preparing for their new lives in the US. But US officials had revoked the visas of many for a variety of reasons. Fighting, excessive use of alcohol, medical problems and anti-social behavior. Vietnam would not take them back and the Manila government maintained that the Philippines was only a transit center. They lived in a stateless twilight zone.

After being defeated at Dien Bien Phu in 1954 and forced to withdraw from Vietnam after nearly a century of colonial rule, France quickly evacuated 25,000 Vietnamese children of French parentage and gave them citizenship. For Amerasians the journey to a new life would be much tougher. About 500 of them left for the United States with Hanoi’s approval in 1982 and 1983, but Hanoi and Washington which did not have diplomatic relations could not agree on what to do with the vast majority who remained in Vietnam. Hanoi insisted they were American citizens who were not discriminated against and thus could not be classified as political refugees.

Washington, like Hanoi, wanted to use the Amerasians as leverage for settling larger issues between the two countries. It was not until 1986, in secret negotiations covering a range of disagreements, did Washington and Hanoi hold direct talks on Amerasians’ future.

In the strange cosmos of life, a funny thing happened along the way. An American photographer, a New York congressman, a group of high school students in Long Island and a 14-year-old Amerasian boy named Le Van Minh had unexpectedly intertwined to change the course of history.

In October 1985, Newsday photographer Audrey Tiernan, age 30, on assignment in Ho Chi Minh City, felt a tug on her pant leg. “I thought it was a dog or a cat,” she recalled. “I looked down and there was Minh. It broke my heart.” Minh, with long lashes, hazel eyes, a few freckles and a handsome Caucasian face, moved like a crab on all four limbs, likely the result of polio. Minh’s mother had thrown him out of the house at the age of 10, and at the end of each day his friend, Thi, would carry the stricken boy on his back to an alleyway where they slept. On that day in 1985, Minh looked up at Tiernan with a hint of a wistful smile and held out a flower he had fashioned from the aluminum wrapper in a pack of cigarettes. The photograph Tiernan snapped of him was printed in newspapers around the world.

The next year, four students from Huntington High School in Long Island saw the picture and decided to do something. They collected 27,000 signatures on a petition to bring Minh to the US for medical attention. They asked Tiernan and their congressman, Robert Mrazek, for help.

“Funny, isn’t it, how something that changed so many lives emanated from the idealism of some high school kids,” says Mrazek, who left Congress in 1992 and now writes historical fiction and nonfiction. Mrazek recalls telling the students that getting Minh to the US was unlikely. Vietnam and the US were enemies and had no official contacts. At this low point, immigration had completely stopped. Humanitarian considerations carried no weight. “I went back to Washington feeling very guilty,” he says. “The students had come to see me thinking their congressman could change the world and I, in effect, had told them I couldn’t.” But, he asked himself, would it be possible to find someone at the US State Department and someone from Vietnam’s delegation to the UN willing to make an exception? Mrazek began making phone calls and writing letters.

Several months later, in May of 1987, he flew to Ho Chi Minh City. Mrazek had found a senior Vietnamese official who thought that helping Minh might lead to improved relations with the US, and the congressman had persuaded a majority of his colleagues in the House of Representatives to press for help with Minh’s visa. He could bring the boy home with him. Mrazek had hardly set his feet on Vietnamese soil before the kids were tagging along. They were Amerasians. Some called him “Daddy.” They tugged at his hand to direct him to the shuttered church where they lived. Another 60 or 70 Amerasians were camped in the yard. The refrain Mrazek kept hearing was, “I want to go to the land of my father.”

“It just hit me,” Mrazek says. “We weren’t talking about just the one boy. There were lots of these kids, and they were painful reminders to the Vietnamese of the war and all it had cost them.” I thought, “Well, we’re bringing one back. Let’s bring them all back, at least the ones who want to come.”

Two hundred Huntington High students were on hand to greet Minh, Mrazek and Tiernan when their plane landed at New York’s Kennedy International Airport.

Mrazek had arranged for two of his Centerport, New York, neighbors, Gene and Nancy Kinney, to be Minh’s foster parents. They took him to orthopedists and neurologists, but his muscles were so atrophied “there was almost nothing left in his legs,” Nancy says. When Minh was 16, the Kinneys took him to see the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C., pushing him in his new wheelchair and pausing so the boy could study the black granite wall. Minh wondered if his father was among the 58,000 names engraved on it.

“Minh stayed with us for 14 months and eventually ended up in San Jose, California,” says Nancy, a physical therapist. “We had a lot of trouble raising him. He was very resistant to school and had no desire to get up in the morning. He wanted dinner at midnight because that’s when he’d eaten on the streets in Vietnam.” In time, Minh calmed down and settled into a normal routine. “I just grew up,” he recalled. Minh, now 37 and a newspaper distributor, still talks regularly on the phone with the Kinneys. He calls them Mom and Dad.

Mrazek, meanwhile, turned his attention to gaining passage of the Amerasian Homecoming Act, which he had authored and sponsored. In the end, he sidestepped normal Congressional procedures and slipped his three-page immigration bill into a 1,194 page appropriations bill, which Congress quickly approved and President Ronald Reagan signed in December of 1987. The new law called for bringing Amerasians to the US as immigrants, not refugees, and granted entry to almost anyone who had the slightest touch of a Western appearance.

The Amerasians who had been so despised in Vietnam had a passport, their faces to a new life, and because they could bring family members with them, they were showered with gifts, money and attention by Vietnamese seeking free passage to America. With the stroke of a pen, the children of dust had become the children of gold.

Counterfeit marriage licenses and birth certificates began appearing on the black market. Bribes for officials who would substitute photographs and otherwise alter documents for “families” applying to leave rippled through the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Once the “families” reached the US and checked into one of 55 transit centers, from Utica, New York, to Orange County, California, the new immigrants would often abandon their Amerasian benefactors and head off on their own.

It wasn’t long before unofficial reports began to detail mental health problems in the Amerasian community.” We were hearing stories about suicides, deep rooted depression, an inability to adjust to foster homes,” says Fred Bemak, a professor at George Mason University who specializes in refugee mental health issues and was enlisted by the National Institute for Mental Health to determine what had gone wrong. “We’d never seen anything like this with any refugee group.”

Many Amerasians did well in their new land, particularly those who had been raised by their Vietnamese mothers, those who had learned English and those who ended up with loving foster or adoptive parents in the US. But in a 1991-92 survey of 170 Vietnamese Amerasians nationwide, Bemak found that some 14 percent had attempted suicide. 76 percent wanted, at least occasionally, to return to Vietnam. Most were eager to find their fathers, but only 33 percent knew his name.

“Amerasians had 30 years of trauma, and you can’t just turn that around in a short period of time or undo what happened to them in Vietnam,” says Sandy Dang, a Vietnamese refugee who came to the United States in 1981 and has run an outreach program for Asian youths in Washington, D.C. “Basically they were unwanted children. In Vietnam, they weren’t accepted as Vietnamese and in America they weren’t considered Americans. They searched for love but usually didn’t find it. Of all the immigrants in the US, the Amerasians, I think, are the group that’s had the hardest time finding the American Dream.”

But Amerasians are also survivors, their character steeled by hard times, and not only have they toughed it out in Vietnam and the US, they are slowly carving a cultural identity, based on the pride, not the humiliation of being Amerasian. The dark shadows of the past are receding, even in Vietnam, where discrimination against Amerasians has faded. They’re learning how to use the American political system to their advantage and have lobbied Congress for passage of a bill that would grant citizenship to all Amerasians in the US.

Before flying to San Jose, California, for an Amerasian regional banquet, Representative Bob Mrazek remised on the 20th anniversary of the bill he had authored. He said that there had been times when he had questioned the wisdom of his efforts. He mentioned the instances of fraud, the Amerasians who hadn’t adjusted to their new lives, the fathers who had rejected their sons and daughters. “That stuff depressed the hell out of me, knowing that so often our good intentions had been frustrated,” he said.